Another TE Model

Or: Tight Ends are the same

To wrap up my projection series (I’m still waffling on whether I’ll actually build something for QB’s), today we’re going to cover the 2025 tight end class. As I did with running backs and receivers, I’ve trained a machine learning model to predict tight end performance.

The model configuration is broadly similar to that of my RB and WR models, and I’m still using the same data sources.1 Tight ends, however, are a slightly more difficult problem to solve; I’ll explain my process below.

Model Performance

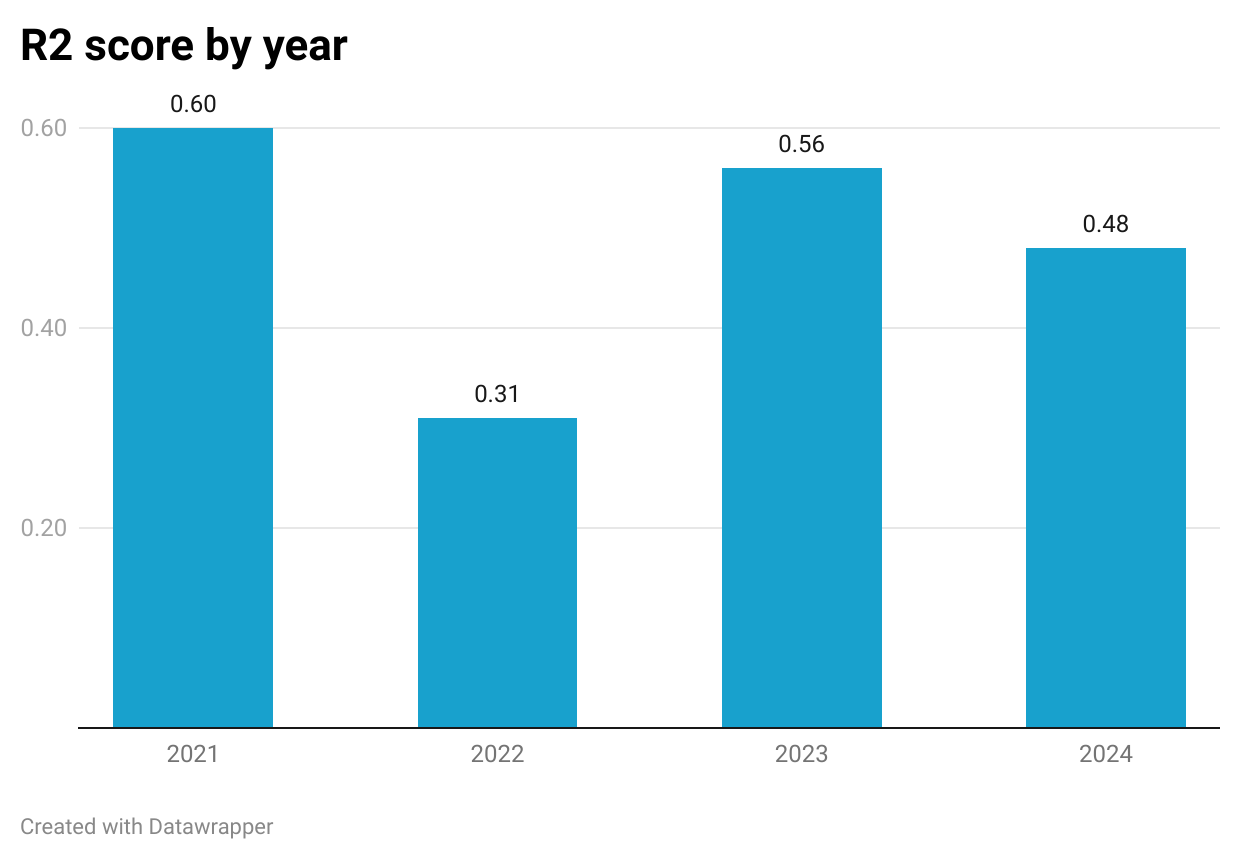

Overall, our Tight End model performs fairly well, though there is some year-over-year inconsistency. It’s still about as good—if not better—than my receiver model, which was also stumped by a single draft class. Here, the laggard class is 2022, with an R² score of .31.

The difference, though, is that the problem class for receivers forced me to rethink my whole strategy: do I adjust my model to raise the floor performance of my worst year, or do I go for the best performance overall? Ultimately, I chose the model that boosted 2023 performance the most, which had real trade-offs. My receiver model now undervalues athleticism, something I might rectify for next year’s class.

This is certainly not the case for Tight End prospects. As our feature importances in the next section show, athleticism is, excepting draft slot, the most important facet of a TE prospect’s profile.

Feature Importance

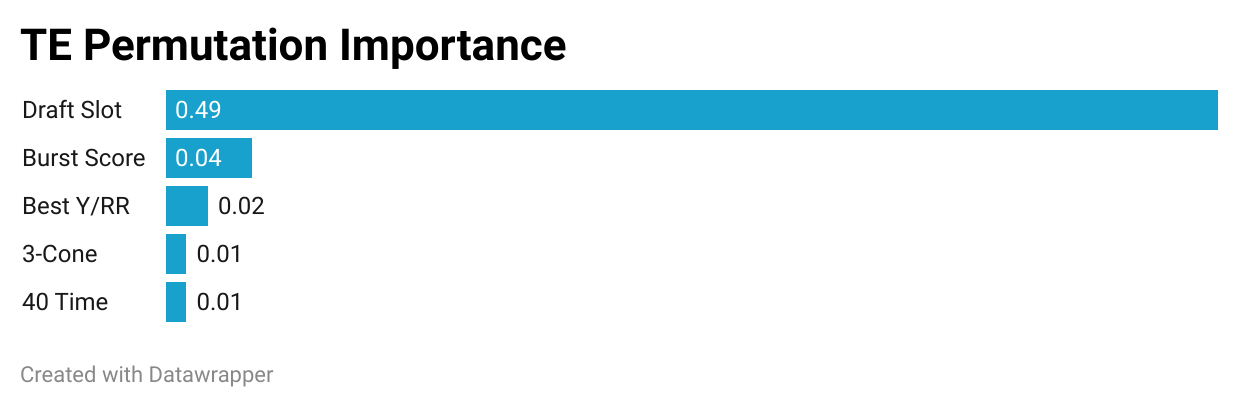

Above are the most important features for our model; though it utilizes other features, their impact is significantly smaller on actual out-of-sample data.2 Our totals above are based on how much removing them hurts our R² score; thus, they don’t sum to one.

As I hinted at earlier, it seems you not only want a TE who’s a combine warrior, but one who’s drafted early. Notably, however, a player’s draft slot is less impactful for TE’s than for other positions, which tracks with conventional wisdom, too.

As far as the combine goes, three areas stand out. A top-flight TE prospect should have good straight-line speed (40 time), agility (3-cone), and explosiveness (burst score). Burst score is simply a weighted combination of a player’s vertical and broad jump, pulled from the ever-useful Pahowdy spreadsheet.3

Great, you might be thinking, but what about actual production metrics? Well, for that we turn to yards per route run (Y/RR). While our model finds some utility in aDOT and air yards, players those stats rate highly could just be running sprints out there, without actually producing. Players Y/RR views as successful, by comparison, are making every snap count.

2025 Results

Above are my three-year PPR projections for the 2025 tight end class. (Click the arrows above to switch between tabs; if you’re on mobile, scroll down to see the full list). I should first note that the upside cutoffs here differ from my RB projections, though the risk breakpoints remain the same.4 Essentially, the bar to clear for Tight Ends is lower, taking a smaller projection to be considered high- or medium-upside.

At first blush, it seems like Mason Taylor occupies his own rung on the ladder, a sort of tier 1.5, if you will. This is driven by his extremely slight advantage in draft position, relative to his peers. Given he was only taken four picks before Ferguson, we can likely chalk it up to a quirk in our model.5

Take away this leg-up, and Taylor’s relative strengths become questionable; however, this is before we consider just how closely bunched together our second-tier TE’s are. Taylor’s Y/RR was a fairly middling 1.1, though it’s worth noting that Ferguson’s was only 1.5, and Arroyo’s was 1.6. In any case, all three of these players are tremendous athletes, whether it be per their combine testing, or tracking data in Arroyo’s case.

We’ve now, it seems, reached an impasse with the 2025 class, our second-tier prospects making it difficult to differentiate between them. Thus, we now turn to the 2021 class, which may offer some clarity.

Much like the ‘25 class, many players from the ‘21 class were projected to score somewhere around 150 points, give or take a couple dozen. What’s remarkable, however, is that, barring a couple misses, the model’s projections were mostly right.

The takeaway is, my model isn’t just blowing smoke when it sees a tight end class as closely grouped together. It’s making its judgments based on years’ worth of data, and is fairly likely to be right.

Does that help us figure out which of Taylor, Ferguson, and Arroyo will be the best NFL player? Probably not, but it does underscore how similar TE prospects can be, and how hyper-fixating on any nominal edge between players can be dangerous. This is especially true for this trio, given each is heading into situations that will offer them ample playing time. My best advice, then, is to take whoever is available latest, rather than singling out a must-have “your guy” among these three.

The Fannin Dilemma

If that doesn’t satisfy you, then I’ll offer up Harold Fannin Jr. His projection is still likely driven by being a mid-third rounder, though he does surpass earlier picks Arroyo and Ferguson in our rankings. We could perhaps chalk this up to an excellent three-cone and Y/RR, with his performance in the latter stat (3 Y/RR) far outpacing his peers.

Again, however, there are caveats: it’s well known that Fannin faced softer competition at Bowling Green. This would generally be fine, but he’s also quite undersized as well, which ought to give us pause due to the demanding athletic restrictions being an NFL tight end requires.

In any case, I think the model has Fannin properly rated, as a highly productive college player with a great three-cone, but question marks about his broader athleticism. Ultimately, which player you choose among these four tight ends is partially about your preferences, but also opportunity cost. Given Fannin is going later than most of his peers on his list, I think he’s a solid bet in the late third of rookie drafts.

Summary

Again, I’m not reinventing the wheel here; my model found the same things to be true about tight ends that many others have before. Yet they’re still useful lessons to internalize, so I’ll list them below.

In short, you want your tight end to be:

Explosive (good broad/vert jumps)

Fast (40 time)

Agile (3-cone)

Efficient (Y/RR)

Picked early

This model isn’t perfect, but it takes a lot for it to be really wrong. One such failure, as you may have noticed above, was Chargers TE Tre’ McKitty, who got a huge boost for being a third-rounder.

McKitty was probably an aberration, though, and validates the importance a player’s draft slot more than it denigrates it. After all, McKitty was a middling athlete, ranked as low as TE13 by some evaluators, and was considered a late-round pick by others. So, of course Tom Telesco selected him in the third round, throwing everything out of whack.

The point is, playing tight end in the NFL is hard, and most late-round talents of McKitty’s caliber don’t make it. The analytical case against drafting TE’s or LB’s early isn’t entirely based on the low value of those positions; it’s also that it takes those guys a long time to get good. Even if the guy you drafted is solid by the end of his rookie contract, you’ll have gotten little value in the mean time.

Therein lies the paradox of tight-end production. The position is ripe with steady producers, and many mid-round tight ends will make it in the league. Yet it’s still a question of when, and even though the three-year outlook is often sunny, you probably don’t want to invest in an asset that’s very likely to decline after year one.

This means that you’re probably better off huffing copium that, say, an Ollie Gordon is going to bounce back in the league than you are drafting Gunnar Helm. Yet even if tight ends are worth less, they aren’t worthless, and a high-floor mid-rounder is often a safer bet than a lotto-ticket running back like Dylan Laube.

Even if your guy never becomes a real asset, if he’s at least perceived as one, that’s all that matters. It’s how I flipped Erick All from waivers into a part of a larger package last year, something I probably couldn’t have done with a UFA RB flameout. It’s how I picked up Jonnu Smith from the scrap heap, and ended up with a more-than adequate contributor.

However people see tight ends, arguably the black sheep of fantasy football, there’s still gold in those hills. You just need to know where to find it.

The model is an NGBoost regressor, using the Normal distribution; the data is pulled from Pahowdy’s spreadsheet and Stathead.

These features still have utility, and include Dominator Rating, aDOT, and Air Yards. This likely means they were useful in distinguishing some edge cases; however, since our R2 score fell by less than 0.01 when we exclude them, their impact was considered too small for the chart.

Note that “burst score” is mislabeled “bust score” on the sheet, a typo that cost me both time and sanity.

Essentially, players with a floor above 200 PPR are considered low-risk; between 100 and 200, medium risk; and anything below 100 is considered high-risk.

I tested this by tweaking what would happen if Taylor was instead picked 47th, and he indeed fell behind Ferguson and Fannin.